Transcript of Panetta Conference in 2004 featuring Fred Thompson and George Mitchell

Challenges Facing Leadership in the 21st Century

The Challenges of Leadership In The 21st Century"World Leadership in The 21 Century" George Mitchell and Fred Thompson

Monday, May 23, 2004

Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Leon Panetta.

[applause]

Leon Panetta: Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the seventh annual Leon Panetta lecture series, presented by Panetta institute, as well as California state university, Monterey bay. I'd like to thank you for joining us this evening in my hometown of Monterey here at the Steinbeck forum at the Monterey conference center. The overall theme of the lecture series, as many of you know, is to focus on the issues and challenges that we face in the 21st Century. Today we live in a very uncertain world.

We and elected officials in this country are confronted with a number of unprecedented issues that challenge our fundamental foreign and domestic policies, from terrorism and September 11 to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, from the Middle East to North Korea, from trade and our economy, the issue of outsourced jobs, the deficits, to nuclear proliferation, to the challenges of health care, and so much more. These issues test our ability to be able not only to lead this country, but to lead the world. The theme of tonight's lecture is world leadership in the 21st century. To discuss these and other issues, we are honored to have two very distinguished former members of the United States Senate. Our first guest served for 14 years in the United States Senate, six of them as majority leader.

He was voted the most respected member of the Senate for six consecutive years. He led the Senate in the ratification of NAFTA and the world trade organization. He was instrumental in the passage of the Americans with disabilities act. He was a leader on environmental issues, re-authorization of the clean air act. He authored the first national oil spill prevention cleanup law, and he led the Senate to the passage of the nation's first child care bill. After retiring from the Senate, he was solicited by the British and Irish governments to serve as chairman of the peace negotiation in Northern Ireland, resulting in an historic accord that ended decades of violence in that area.

For his service, he received the presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award that is awarded by the U.S. Government.

At the request of President Clinton, former Prime Minister Barak, Chairman Arafat, the Senator served as a chairman of the international fact finding Committee on Violence in the Middle East. The resulting recommendation, known as the Mitchell Report, won the support of the Bush Administration, the European Union, as well as many other governments.

After having dealt with crises in Northern Ireland and the Middle East, he was prepared, well prepared, to become chairman of the Disney Corporation, which tests all of his diplomatic skills.

He earned his law degree from Georgetown University, later served as a trial lawyer in the justice department. He was appointed U.S. Attorney, later moved on to become a U.S. District Court Judge in May.

He's the author of four books, currently with the national firm of Piper Rudnick. I've had the opportunity to work closely with him in Congress and as chief of staff.

He is truly an outstanding public servant in this country. Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming the Honorable Senator George Mitchell.

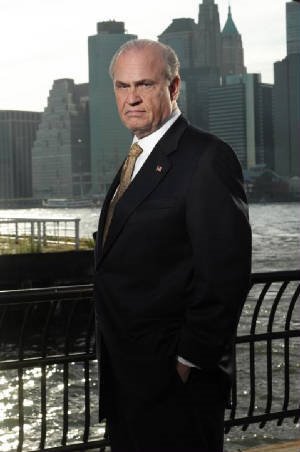

[applause] Leon Panetta: Our second guest this evening has an equally formidable background in the realm of politics. Although he is known to much of America through his appearances in 18 motion pictures, and as the actor currently playing the District Attorney in the highly acclaimed television show "Law and Order," he has also proven he can work without writers.

He has a distinguished career in public service that dates back to his role as an assistant counsel in the Watergate investigation. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1994, reelected in 1996, receiving more votes than any previous candidate for any office in the state of Tennessee's history, something he reminds Al Gore about every other day.

As a Senator, he served on the Senate Committee on Finance, Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, and the National Security Working Group. In 1997 he was elected Chairman of the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, and there he sought to produce a smaller and more efficient and accountable government, holding hearings on topics such as improving the regulatory process, reforming the I.R.S., and worked on the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and missile technologies as well. He proposed legislation to curb the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction by China and other countries, and advocated a streamlined export control policy to try to protect our national security. In 2002 he was elected to the prestigious Council on Foreign Relations.

A native of Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, the Senator received an undergraduate degree in philosophy, political science, and a law degree from Vanderbilt University. Two years after graduating from law school, he was named an Assistant U.S. Attorney, and at the age of 30 was appointed Minority Counsel to the Senate Watergate Committee. He's the author of a Watergate memoir, "at that point in time," and was recently named a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. I've also had the opportunity to work with him as Chief of Staff and more recently, work with him and Paul Volker in an effort to attract good people to service in government. Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming Mr. District attorney, former Senator Fred Thompson.

[applause] Leon Panetta: welcome, both of you, to the Monterey Peninsula. Let's begin by talking a little bit about the broad subject of leadership in the 21st century.

Last century we defeated fascism and communism. In order to do that, we had to build a strong defense. We had to build strong alliances. We built NATO, helped create the U.N.. This century, the threat is obviously terrorism.

We have a strong defense, but can we win without building strong alliances? Has Iraq hurt our credibility, or our ability to develop those kinds of alliances? George Mitchell: It clearly has had a negative effect to the present time, but the situation surely can be redeemed. I think that the North Atlantic alliance is arguably the most successful political and military alliance in modern human history, and accounts for much of the post-world war ii growth, prosperity and spread of democracy. Certainly Europe, in concert between us and Europe, to other parts of the world. That relationship is under strain. There are obviously differences not only about Iraq, but exacerbated by the situation in Iraq.

But they surely are not final and irredeemable. I think with the proper policies, the proper approach, we can repair the breaches that have occurred, and we can work closely, as we indeed are, with many of our European allies in other areas, in the war on terror. That will be essential because it is clear that traditional military force, while an absolutely essential component of the preservation of our defense and security, cannot by itself be completely successful in the struggle against the modern scourge of terrorism. That takes effective intelligence, perhaps most importantly, effective police - effective police work around the world.

That comes from close cooperation, coordination with other countries in the world. When the President addressed the nation and Congress in his stirring address after September 11, he pointed out that Al Qaeda operates in 60 countries.

A few months later in his state of the union address, describing the successes in the war against terror, he said arrests had been made of Al Qaeda operatives in seven major cities. Only one of them was in the United States.

It was Buffalo. The other six were all outside the United States, so it points up, his own words pointed up the necessity of cooperation with others in this conflict, and so we are the most dominant economic and military power.

We will continue to be for certainly as far as human beings can see. But even with that vast power, we cannot, in my judgment, successfully prevail without cooperation and support from our allies. I believe we can get it, and I hope that we will. Fred Thompson: Leon, we shouldn't have to worry about whether or not we could go it alone if we had to. Hopefully it doesn't come to that. We should strive to avoid that, if for no other reason because in any democracy, I think the people's willingness to sustain protracted hostile and unpleasant activity is limited, and I think that when there is a lack of national support, it's more difficult to maintain the support inside your own country, when people see that. However, it's not exactly like we're in the habit of doing that. I think we've gotten a bit of a bum rap because of that.

We certainly had a coalition in 1991. We went to Iraq. We were part of a group with regard to Kosovo. There are over 30 countries involved in Iraq today, so it's not like we're going out and looking for ways to become unilateral. The real issue is, we're the world's leading power and the world's leading target. What about those instances when try as we must -- and admittedly we could have done better in our diplomacy this time around, but let's say, try as we must, we see a situation that we think is of vital importance to us, and we cannot get the French and Germans, for example, to go along, or the united nations, who is usually, you know, relying upon the United States to be the end of the spear when we agree on activities to do together.

What about it then?

Obviously none of us will want to give anyone else a veto over United States actions, that it feels like it needs to take in its own self-interest, so the question becomes instance by instance, what is really in our self-interest and what is worth going it alone for. We've been given a lot of blame recently. I think some of it justified, a good deal of it is not, but you have to look at the other side of that equation.

Why is it that some of the European countries try every way they can to not cooperate with us?

Why were the French and Germans and Russians trying to get economic sanctions lifted from Saddam?

Why were so many leaders around the world apparently in on the food for peace scandal that we're seeing now?

So there's some blame on the other side. Why were so many countries doing deals with Saddam for oil before all this broke?

So there are two sides to it, and it all comes back to situation by situation, and our need to properly evaluate each situation as to what's in our legitimate self-interest and how far we're willing to go in protecting it. Leon Panetta: Let me ask you about -- the President has said, the Solicitor General said in arguing before the Supreme Court, that we are a nation that is at war and admittedly we are losing men and will on the battlefield, but we are also a nation that when we are at war has demanded shared sacrifice by the American people. But we have not been asked to pay for this war and we're looking at a price tag that could run anywhere from $150 to $200 billion. Most of that's borrowed money. We have not been asked -- we have a military force that's deployed almost everywhere in the world. You're talking about a deployment of 130 to 150,000 troops in Iraq for an indefinite period of time, but we've not been asked to institute a military draft.

And we are asked not to pay attention to the pictures of caskets that return from Iraq. Can we be a nation at war and somehow pretend that that war is not real, and demand sacrifice? Fred Thompson: well, I don't think anyone is trying to avoid recognition of the caskets that are coming home. But I agree that we have not been treating this as it is, a war. I don't think the average person feels that way. I think we could have done more to spread the burden. I think, for example, this would have been a great opportunity early on to say ok, we don't want to do it, but now we're going to have to have a tough energy policy.

The source of a lot of this is our dependency on oil from that part of the world, so we're going to have to give something, business is going to have to give something, and we're going to need a better energy policy.

So yeah, I think we could have done a lot better in terms of sharing the sacrifice. So it makes it very important that we have some fiscal policies, in order to carry on those things.

Let's take, for example, that this was a just endeavor in Iraq, which I happen to agree with. But it's going to be extremely expensive. Homeland security, we just merged 22 departments of homeland security. It's going to be extremely expensive.

We don't realize how much we're going to have to do in terms of protecting our infrastructure. Most of it's in private hands in this country, all the railroads and rail lines and highways and bridges and things of that nature, nuclear plants and things of that nature.

The cost is going to be tremendous. When a long drawn-out protracted war that our leadership has not properly explained to us yet, we've had war declared Against us back, the first time was 1996 and then 1998 again by Osama Bin Laden. Nobody paid much attention to it.

We're going to have to pay for it.

That means we're going to have to have very sound fiscal policies to keep our economy churning, and that's why George and I will launch into another debate as to what sound fiscal policy is, and the right mixture of taxes and spending. Our non-defense discretionary spending from 2001-2003 went up, what, 15%. We cannot sustain the spending side. Others say we can't sustain the tax cuts.

Whatever, we've got a big deficit, and it's going to get bigger when the retirees retire, so it all mixes together.

We've got to pay for it, it's going to be extremely expensive, but we're not doing the things on the fiscal side that are necessary to put us in the economic position, strength wise, in order to get the job done. Leon Panetta: George. George Mitchell: we probably could have a vigorous debate on what is the right fiscal policy. But I think we can all agree on what is not the right fiscal policy. And that is to spend $150 billion on the war in Iraq while providing huge tax cuts to the wealthiest Americans here at home, and taking --.

[applause]

And taking a $500 billion surplus to a $500 billion deficit. As I said, we can debate about what the right thing to do is, but I think that clearly is the wrong thing to do.

On the concept of sacrifice, it is one of the fundamental problems in any democratic society, indeed in life in general, that sacrifice is never equally distributed.

In every war, some are called, some are not. Of those who are called, some fight, some do not. Of those who fight, some die, some do not. There is no policy, government or otherwise, which can ensure the completely equitable distribution of sacrifice in any society. But there is also a strong and overwhelming national feeling that there ought to at least be an effort, even though perfection cannot be attained, or full success. I think what's lacking now is the complete absence of any effort to achieve any distribution of sacrifice. I agree completely with freed about energy policy.

Our country desperately needs one. Everyone agrees on the need. Very few agree on the solution.

Therefore, the easiest thing to do is to let it pass. I do not favor reinstitution of the draft because while it does appear to pose an attractive alternative to the current situation in terms of distribution of sacrifice, throughout our history, conscription has been plagued with inequities of its own. There's no way we could draft every military eligible person in the country, and therefore you begin right away with the fundamental question, who gets drafted, who gets exempt.

To this day we're still arguing in our country about who served in Vietnam, why they did and why they didn't.

And so in the guise of solving one problem, you create another, and one of the things I learned in Washington is that the most effective legislators were those rare few who had the wisdom to anticipate the unintended consequences of what they were trying to do, that is, they thought about the problem that would be created. Never forget that the solution to every human problem contains within itself the seeds of a new problem.

That would happen if we reinstituted the draft. Leon Panetta: I'm well aware of the Ted Koppel controversy. But, don't you think we are entitled to share in the pain of those losses? Fred Thompson: yes. But I think it's a waste of time and energy to have a big controversy over that, but the question gets into motivation and I don't know what's in Ted Koppel's mind.

I tend to be a little bit skeptical myself, but it's not enough to, you know, tear the sheets up over, in my opinion. I think we need to all recognize that what's happening there, and the full picture of what's happened, and the reason we're there, as well as the difficulties we're having while we are there. Leon Panetta: let me ask you about Iraq. We've had a rough few weeks in Iraq.

We've had the bloodiest month that we've ever had, in April. We obviously have now these pictures of abused prisoners. That isn't going to help our situation with regards to the Arab world. In Fallujah, we are now beginning the process of turning power over to former members of Saddam's army, some of whom have been members of the Republican Guard.

We fought this war to get rid of Saddam Hussein and those who supported him and now we're returning power to his generals. What's wrong with this picture? Where did we go wrong, and what do we need to do to fix the situation? Fred Thompson: I'm very concerned about this. There's a lot wrong with this picture. Was it napoleon who said if you say you're going to take Vienna, you'd better go ahead and do it, and we are looking weak right now.

I don't know what's going on there, what the strategy is, why they're doing what they're doing, bringing in a former Saddam general, television cameras, people applauding and so forth, and the next day I hear, well, this guy is probably not going to be the guy anyway.

The whole situation is a great challenge. You've got to make a decision between two very bad choices. It looks to me like if they take Fallujah, that it's going to play Al-Jazeera, you know, forever. And it's going to be rough and it might cause uprisings in other parts, and it might prove to be disastrous.

On the other hand, in my opinion, if they do not take Fallujah, that is guaranteed -- and bring in Saddam's old generals, that is guaranteed to prove disastrous.

A fellow who spent time down there and whose opinion I judge, I value highly, has said that the one thing we need to remember is that we must keep the Shi'ites on our side, and I just don't see how that does that. They are talking tactics as well as strategy, I guess, in terms of battle situations down there, but mistakes have been made. Sound like Nixon, don't I? I think -- it seems to me war is a succession of mistakes. Mistakes were made in the Korean war, mistakes and setbacks came about in world war ii. Certainly here, we probably went in without enough troops in retrospect, certainly now it seems like a no-brainer, although that's still debated. Some people think that running off the old Saddam military was a bad idea. As conventional wisdom, maybe that's true.

I don't know.

Underestimating the difficulty of pacifying the place clearly was a mistake, although I don't remember that many commentators and experts before the fact predicting that this was what's going to happen.

A lot of people thought we shouldn't go. A lot of people thought we were going to meet more resistance than we in fact did. We made a mistake as to the strength of the resistance to start with. It was easier than what we thought, turned out to be. But regardless, if you're carrying out this operation, it's your responsibility not to make mistakes, if they can be avoided, and that was a mistake. So we can spend a lot of time looking backward, but looking forward, I believe that over a period of several years now, we have slowly but surely developed a reputation, not as a country that's looking for a fight or looking to unilaterally invade folks for the fun of it, but if we pull out when things get tough, as we did in Somalia, as we turned around in Haiti, the port there, as we did in Lebanon, a lot of people interpret our leaving when we did in Iraq in 1991 in retrospect, as weakness. The many times we've been attacked from African embassies to the attempt in the airport in Los Angeles, the following year, to the following year of the world trade center before, and our tepid responses to all that. All of that has led us to a situation where people are expecting us to do that again and if we do that again, it's going to make for a much more dangerous situation.

That's a fear for us.

That's a theater of war there. If we got out of war tomorrow and had no involvement forever, it would be a terrible blow to us, but it would just simply change the theater to another one.

Or several more, including the possibility of a very real possibility -- and I think probability, of a theater of war in this country, many cells are here already.

Some think, you know, waiting to be activated. I do not know. So it is a problem. It is a mess.

But it is not one that I think we asked for. It is one that we're struggling to come to the right answer to, and I think pulling out of there and running and not doing what's necessary to be successful there -- and at least give those people an opportunity, ultimately they've got to be the ones to decide what kind of country they're going to have, but giving them an opportunity to live in a different kind of society now that Saddam and Uday and Husay, how soon we forget, now that they're not running things anymore. George Mitchell: First, let's identify what went right. The military, the active military phase of the operation was clearly well planned and executed.

That only pointed up the dramatic contrast with the absence of effective planning and implementation on the effort to secure the peace. Leave aside the whole question of whether we should have gone in and if we did, did we go in on a pretext or on a genuinely proper basis, but once there, what went wrong?

Of course the first and most fundamental problem upon which everything else is built or from which everything else flows, as Fred pointed out, is the inadequate intelligence and what appears to be the enormous amount of self-delusion that occurred within the Administration.

We would be greeted as liberators, flowers in the streets, the Iraqis are going to pay for the reconstruction themselves with their own money.

There's a long litany of that, grounded in fact in part on an excessive reliance on expatriates, some of whom had not been in Iraq for decades, who had direct interests, financial, personal, political ambitions, and who clearly did not provide a complete and accurate picture of what could have been expected.

On that delusion, the following errors in judgment occurred.

First, the effective stiffing of the U.N. and others. The attitude that Iraq was a prize which we had won from which others should be excluded, rather than Iraq is a burden which we should invite others to share. The refusal to give the U.N. A meaningful role. That has now been completely reversed. The Administration's position is the exact opposite of what it was a year ago, and we are asking the U.N. To take over the political process, and in fact Ambassador Barzami will go there in the next few days to select. He will personally select the new transitional government to which sovereignty will be transferred in a limited way on June 30. The second mistake was the total disbandment of the Iraqi army and all Iraqi security forces. Ambassador Bremer's first major act when he took over last year. It not only removed from Iraqi society what had been a large and active and influential institution, thereby creating a political vacuum, it immediately created a large army of hundreds of thousands of men who had once had status in Society, had jobs, who now were unemployed, unable to feed their families, and who were easy prey for those recruiting insurgents, and it's quite clear that they have led the effort. Now we've again reversed that policy and we're moving toward what we should have had, a sensible vetting policy to identify and disqualify the top leadership but not the entire army and the entire security force. So I think those changes are under way and that is one reason why I think the policy can be redeemed.

I do agree with Fred that we simply can't leave. In the memorable phrase that Bob Woodward tells us Colin Powell used with the President, he said--you break it, you own it. Well, we broke it, we own it.

As difficult as that might seem, what we need to do is leave as soon as we possibly can, when we have created a circumstance in which the people of Iraq have a fair and reasonable chance to create a society of their own choosing.

And one final mistake was to set the expectations so high. Who can now recall, it seems like decades, not months, that the Administration was talking about a model democracy that would cause the dominoes to fall in a democratic way throughout the Middle East, which would serve as a model for everyone. There was no nation of Iraq before 1921. For 400 years previous to that, under the Ottoman Empire, the Kurdish north, the Sunni center and the Shi'ite south had been separate districts. A British civil servant placed a large map on the table in Paris in 1921 and he drew a series of lines, creating a nation which had never before existed.

He also, incidentally, same guy, same map, same day, created Jordan, which had never previously existed. The British were not interested in the wishes or the hopes or the needs of the people who lived there. They had their immediate political problems which they were trying to solve. And so this is tough going.

This is not easy to do, and the reality is if we can create a modest opportunity for them to live, probably in some kind of federated democracy that won't look anything like the American system but will give people a chance to decide their own lives, we should count it a success and leave at that time, but not before. Leon Panetta: let me ask you on the weapons of mass destruction, because we all -- when I was in the white house, we were briefed on the existence of weapons of mass destruction. I'm sure you had briefings that were very similar to that, and Bob Woodward's book, George Tenet says when the President even raises a question about it, that it's a slam dunk, that weapons of mass destruction are there. And that obviously we found out that they were all wrong. How could our intelligence, how could our intelligence be so wrong about something so important? George Mitchell: First, let's be clear. One of the things the Administration skillfully did was to conflate three separate categories of weapons into a single slogan, weapons of mass destruction - nuclear, chemical, biological.

There was no evidence that there was, last year or the year before, an active nuclear weapons program, and all of the evidence since then has confirmed that.

There had been evidence back in 1991, but as is clear, it had not been reconstituted. So there was no basis for the statement by Vice President Cheney that Iraq will have a nuclear weapon very soon.

There was evidence, substantial evidence, that in 1998 and 1999 when the U.N. Inspectors left, Iraq had previously accumulated a substantial volume of chemical and biological weapons which they had not credibly accounted for as either destroyed or consumed or otherwise disposed of.

So the fair argument, the truthful argument, was that the united nations had certified that Iraq has previously possessed chemical and biological weapons.

Iraq has not accounted for the disposition of those weapons, and it is fair, therefore, in the absence of such evidence, to deduce that they still exist. That was the fair argument.

The problem was that the Administration, of course, felt that that would not be enough to generate the kind of support for the war that existed, and the arguments went well beyond it.

How could our intelligence be so wrong?

Well, first, Leon, as you well know, intelligence is not a perfect mathematical accumulation of facts.

It's highly subjective. It's contradictory. It's vague. It's ambiguous.

Added to that, the fact that our human intelligence capacity has atrophied as our intelligence gathering capacity has grown. So the result is we can intercept millions of telephone conversations but we don't have many people on the street corner in Baghdad reporting to us. That's a real problem which I think has to be corrected. And third point, the volume of information collected is so much that our capacity to translate, analyze, interpret and collate it, has not kept pace. So you've got mountains of material and a very slow rate, it's not in real time, that it's developed.

So I think all of those things contributed to the failure. Leon Panetta: we've got just a few minutes before the break, but I'd like to give you a chance, Fred. Fred Thompson: I agree with George. I think it's a matter of lack of adequate human intelligence and lack of adequate analysis. We let down our guard after the Cold War in many respects.

Intelligence was one of them, especially human intelligence. Our military budget, our military personnel cut back and so forth, all for some years, led up to September 11. It takes a lot sometimes to get our attention. Osama had declared war on us. We'd been attacked several times, abroad usually, weren't paying that much attention. That's the intelligence background in a nutshell.

On the weapons of mass destruction, the people who thought there were weapons of mass destruction include, besides President Clinton, our C.I.A. The business about Saddam being capable of reconstituting his nuclear program came from a national intelligence estimate. That was not made up by Dick Cheney.

All the foreign intelligence allies that we have came to the same conclusion. All of the members of the Senate select Committee on intelligence that I served on, that I know of, came to the same conclusion. Some of the President's most vigorous critics now said at that time that Saddam posed an imminent threat at that time, including myself.

We were apparently all wrong about that. The jury is still out and maybe he hasn't had them for a while, maybe they're in Syria, who knows. But the significant thing is, I believe, is that if we had left Saddam alone, he still had his infrastructure.

He still had his scientists. He still had his capability. He still had his desire.

I can't prove this, but in my opinion if we had not gone in there, there's no question, in my opinion, in a few years, Saddam would have had nuclear capability to go along with what he admitted in terms of having chemical and biological. Leon Panetta: Let me just give you a few seconds. George Mitchell: It is true that the national intelligence estimate said Iraq had the capacity to reconstitute its nuclear weapons program, but that's not what Vice President Cheney said. He said they have an active nuclear program and they will have nuclear weapons fairly soon. If he had said what the national estimate said, he would have been completely accurate.

One final point on the intelligence. We relied upon the expatriates who told us what we wanted to hear and that is human nature. Every time somebody says something to me that is a repeat of something I said elsewhere or I previously believed, I say boy, that guy is really smart. Leon Panetta: We've come to the conclusion of the first part and it goes very fast when we're talking about these kinds of issues. We'll take a 10 minute break and then we'll return for your questions.

Thank you. [applause] Leon Panetta: If I could, I'd like to take a moment before we begin the second half to introduce our question review team. They're the people who are responsible for reviewing the questions this evening, and if you'd please hold your applause while I introduce the entire group. They're Carolina Garcia, who's the Executive Editor of the Monterey County Herald. Fran graver, our veteran question review team member. Pete Elfish, another veteran question review team member. Jody Jones, anchor for Fox News.

Thank you. [applause] Leon Panetta: I'd also like to take a moment and ask the students who attended the afternoon session--we do an afternoon session with students from the central coast and they have the opportunity to ask our guests questions; we had a great session today-- if I could ask them to please stand.

These are students from the Monterey peninsula college, and Santa Catalina school. One high school, and our local community college.

[applause] George Mitchell: The constitution does not define cruel and unusual punishment, but surely it must include these students having to listen to two ex-politicians on the same day. Leon Panetta: Our first question deals with the Middle East, and I wanted to -- I want to follow up on the question because obviously, what we're seeing today, Ariel Sharon is the -- his party did not support his proposal to basically withdraw from Gaza. Recently, President Bush made what looked like a fundamental shift in Middle Eastern policy, by recognizing the Israeli claims to major settlements in the west bank. And the U.S.-- I guess the question I wanted to ask you, George, having spent your time there, has the U.S. backed away from the peace plan that was agreed to in the past, and has it lost its ability to be a fair broker between Israel and the Palestinians? George Mitchell: The Administration says it has not backed away from the peace plan, the so-called road map, which incorporates in its entirety the plan that our commission delivered to the President when we completed our work. It remains to be seen whether the recent action was, or becomes, a part of a more comprehensive effort to push the road map, which I believe offers some opportunity for progress, although it's a very difficult situation.

If it is not that and if it is merely a single isolated act in response to an Israeli initiative, then it is not likely to advance the process further down the road.

I spent a week in Israel just a short time ago, with both Israeli and Palestinian, political and other leaders. There is a sense of pessimism. I would call it consensus that not much is going to happen this year. We have a presidential election in this country.

As you know, Sharon has not only had this difficulty with his own party, there are two current criminal investigations under way in which there's usually some discussion of whether he will, or a member of his family, will be indicted. On the Palestinian side, there has been a disintegration of the authority of the Palestinian authority itself. That is, the governing institution, resulting in a dramatic increase in crime, the dissolution of law and order among large segments of the population, and within the Palestinian authority, a sharp decline in the authority of Chairman Arafat. He's alienated many of his own leaders, the part of the group that's been with him for so many years, so with the crisis of leadership, there are questions of leadership among Israelis, the American election, there's a sense nothing is going to happen this year.

But I come away with one note of optimism. What I did detect is an attitude among the public on both sides that is quite similar to what existed in Northern Ireland just before we were able to get a peace agreement there. I've been asked thousands of times, how did you get a peace agreement in Northern Ireland after 30 years of war and so many failed efforts? And my answer is that the public on both sides became sick of war. They became weary of the overwhelming essential of fear and anxiety that pervaded all segments of society and made a normal life impossible, and I think that's happening now among Palestinians and Israelis, a sense that they can't get what they want following the present course.

I think that's right. The Israelis want security. The Palestinians want a state.

I believe that in the end, neither can achieve its objective by denying to the other its objective. The Palestinians will never get a state by the suicide bombing of Israelis. Each suicide bombing is not only morally reprehensible, it's politically counterproductive and retards progress toward a state. So they're not going to get a state until the Israelis have security, and I don't think the Israelis can have any sustainable security until the Palestinians get a state, and I think that realization is dawning, and I hope and pray they will move toward the accommodation necessary so that each will have its objective and they're not going to become friends or trusting. They're still not that in Northern Ireland.

But the end of active conflict, the end of killing, I think, has to be the immediate objective before you move on to the second stage of political stability and the third stage of genuine reconciliation. Leon Panetta: can the U.S. play the role -- George Mitchell: Yes. Yes. The United States is committed to Israel.

Have been since the day it was founded. We are openly committed to its survival as a sovereign state with defensible borders. But we are also publicly committed, as President Bush has said, to a Palestinian State.

It is true that the overwhelming majority of Arabs believe that the United States is hopelessly biased in favor of Israel, but that doesn't disqualify us from acting because they recognize that no one else can do it. Think about the fact, every time something bad happens in the Middle East, most Arab government leaders hold a press conference to ask for greater American involvement.

They don't say we want the Americans to go away. They say the problem is, there hasn't been enough involvement by the United States.

So they recognize that yes, we are committed to Israel, but also, yes, the United States government is the only entity with the capacity to create the conditions to which an agreement can be reached and most importantly, to guarantee implementation.

One final point. It comes down to money. We all celebrate Camp David.It was a great success. The glue that holds Camp David together was the American guarantee of $3 billion a year minimum to Israel and $2 billion a year to Egypt. 25 years, we're still paying it out. 125 billion dollars have been paid to guarantee that implementation. You American taxpayers are the implementers of peace in the Middle East when it comes.

[applause] Leon Panetta: Senator Thompson, the U.S. did a pre-emptive strike in Iraq because of the threat of weapons of mass destruction. How difficult will it be for the U.S. to ever get support again for a pre-emptive strike against another country? Fred Thompson: Well, I still think it depends on the circumstances that the United States is faced with and how effective we make our case about those circumstances.

I think part of our problem in this case was that so many of our European friends as well as other people around the world did not be appreciate or believe the nature of the threat, that terrorism essentially was our problem, we were the number one target, and we didn't make an effective enough case as to the nature of the situation.

I think unfortunately, the war will be seeing that play out, in other ways, as the Spanish have. I think that had more to do with their support than just their support of us in Iraq.

And Bali -- other places, of course, we've already seen. But I think there are two parts to it.

First, our allies, as I was alluding to earlier, I think we've got to make the case, we've got to have much better intelligence, and as you pointed out earlier, intelligence is never perfect. It's an imperfect science, and ours is certainly not where it should be.

There are all kinds of scenarios in the future that would present terrible quandaries for all of us. We're all focused now on this one place.

It will be resolved one way or another before long. What kind of world are we going to live in afterwards?

Are we going to have a situation where we cannot act unless we have 100% intelligence that is unassailable, which I think probably virtually never happens.

Suppose someone comes in and tells the President that they have information of something that's about to happen and particular place and location of the most severe consequences.

But the source, there's only one source, and the source of that has a spotty record, sometimes he's been wrong and sometimes he's been right.

What do you do in a situation like that?

Those are the tough decisions we're going to be required to make more than anybody because we're the number one target and we're the leading nation.

So we're going to have to work effectively and try to make our case as best we can to our allies.

On the other hand, I think that some of our allies have to have a different attitude themselves about things. I think there was certainly mixed motives and most of them not very laudable in terms of some of our European friends with regard to Iraq. I think they had self-interest, self-dealing. I think that they were more than happy to kind of stick it to the United States.

They had been chafing for a long time because of -- chafing for a long time because of everything from our turning down the Kyoto Treaty to back even before the Bush Administration. There's been talk of American arrogance and that sort of thing. So hopefully, they will see what Thomas Friedman wrote about in the "New York Times" a while back.

He said, this is a war between the forces of order and the forces of disorder, and if the forces of order do not understand this and pull together and come together and get over their petty differences, we're going to be in deep, deep trouble, because the forces of disorder are everywhere. They're organizing, and they can be tremendously destructive and a handful of people can get their hands now on the technological resources to kill thousands and thousands of people. We don't even talk about weapons of mass destruction anymore, out of the context of Saddam Hussein.

But they're still out there, they're proliferating, we're always finding new countries and rogue nations that have stuff that we didn't know that they had, so that's the kind of world that we live in, and the United States and our allies, better learn how to work together and confront this problem jointly, because as I say, it is everybody in the free world's problem. Leon Panetta: You're both lawyers, and you're a former Judge. What are your feelings about holding American citizens and denying them basic rights in the name of fighting terrorism? I think there was a case that was argued within the last few weeks that involved holding a U.S. citizen and declaring him an enemy combatant and therefore depriving him of right to counsel, right to a hearing, et cetera. Is the executive branch justified in doing that in the name of war? George Mitchell: No, it is not.

There are two cases. The facts are different. In one, the American citizen was captured in Afghanistan in a circumstance that can fairly be described as combatant.

In the other, another American citizen was arrested in Chicago. I don't believe in either case any American, including the President, has the authority to deprive a citizen of his constitutional right simply by declaring him to be a noncombatant.

[applause] George Mitchell: The essence of liberty and the entire concept of equal justice under the law rests upon the premise that we're a government of laws, not men. The founding fathers went to great lengths to ensure that no person would have the power that this President now claims. There's an argument to be made with respect to the person captured in Afghanistan. I believe there can be no credible argument with respect to an American citizen who's captured in Chicago.

The constitution does not have any qualifications, any conditions, does not set forth any circumstances in which the constitutional rights of any American citizen can be so denied and abridged.

Remember, held in prison, not able to see an attorney, not able to see anyone, not charged with any crime, simply held indefinitely in prison. Now, it's easy to say terrorism, threats to our society, all of that may be real. But I think that the constitution in this case is clear.

I hope very much that the supreme court will reach the conclusion that as powerful as the President is, he does not possess the power to deprive any American citizen of his or her constitutional rights.

[applause] Fred Thompson: That of course begs the question, what is his constitutional rights? I think the history of warfare and our judicial system, from what I recall, weighs in on the side of the President in this case. I think that President Roosevelt, for example, exercised these prerogatives under the war making powers and the constitution given to the President.

The real question is whether or not this is a typical kind of situation. Obviously the President can't violate any citizen's rights as such, or whether or not this is a wartime situation, where the rules of the game are totally different, and if someone can be detained just like a prisoner of war, until the hostilities are over.

Incidentally, if they were tried here and sentenced, they would probably wind up serving a lot more time in confinement than under their present circumstances even though hostilities are probably going to go on a long time, they'll probably get out sooner. The situation involving the Chicago case is Mr. Padilla. His parents were, I believe, citizens of Saudi Arabia.

They were in the United States briefly and this is not relevant legally, but he was born in the United States. He'd just come back from Pakistan. The allegation is that he was planning to -- he and others, to set off a dirty bomb here in the United States.

I think the resolution to this -- the problem that I have with it is that there needs to be a procedure to cover situations where someone is captured and held in error.

Everyone ought to have the right, like I think article 5 under the Geneva Convention, ought to have the right to come before a judge and say you've got the wrong guy and I can prove it.

And I think that's where the Administration made a mistake and I think hopefully that's what they're gravitating toward. But simply showing some threshold, not as in a regular criminal case where you have to prove a criminal case beyond a reasonable doubt, but at least some kind of prima facie showing that ok, we got him, here is where we got him, here were the circumstances and we got a right to keep him, and at least press that threshold.

I'm uncomfortable with anybody, even under wartime circumstances, if they're not in an active combat situation abroad, being held indefinitely without some kind of judicial review, but I don't think it's required to have the same kind of judicial review that you have in a typical criminal proceeding. Leon Panetta: George, what obstacles do you foresee for the Kerry campaign in the upcoming election? George Mitchell: Well, to begin with, 180 million of them. That's the amount that the President's campaign has raised.

And it's been an amount without precedent in American history at this stage of the campaign, so since it's never occurred, no one can be secure in predicting what the outcome is going to be.

Secondly, it's quite clear that there are certain disadvantages that accrue to incumbents because they have to actually do things and make decisions, but there are also enormous advantages that accrue to incumbents. Leon, you ran as an incumbent every time but once, and so you know what the advantages are, as Fred and I do as well. I think it's going to be a very close election. I think the country is about evenly divided.

Right now my guess is that it will go down to the wire, and it will be very close.

I think that Kerry faces the challenge of a financial disadvantage, a non-incumbent, and also the importance, the need to present a credible alternative to the President, particularly in the area of terrorism and conflict and strong leadership. I think he can do that. I am of course an active democrat, but Fred and I, I guess, will cancel out our votes this fall. Fred Thompson: I was about to say, good to see a couple of old Clinton supporters decrying money in Presidential politics. [applause] George Mitchell: all I can say, Fred, is that Bush outspent Clinton and so did Dole. Fred Thompson: Inflation. Leon Panetta: Let me ask you, there is a lot of money obviously involved not only in the Bush campaign, but Kerry is out raising the same kind of money. We've got television ads appearing. They're beating the hell out of each other.

They're accusing each other of virtually being unpatriotic, that both have not served this country well, and I think it was John McCain who finally said, you now, the Vietnam War is over, for goodness sakes, let's move on.

If they're beating each other up this badly now, I mean, in six months, what is the impact of that in terms of the American people's attitudes towards the Presidential race? Fred Thompson: The American people have shown boundless capability to absorb unprecedented onslaughts to their sensibilities in politics. And I guess this will be no exception.

I don't know what -- obviously, what they're doing is -- you know, the thing that bothers me most about presidential politics and the mud slinging, I'm sure before it's over with, they'll have enough -- each side will have enough money to sling about all the mud they want to, so that doesn't -- but it's that we have to wait until the presidential campaign is over before we can have some serious discussions about serious problems.

A presidential campaign is the last place in the world you're going to have a serious discussion about a serious problem. We're sitting here watching ourselves walk off a cliff, you know, in the out years, past the projections that we're all talking about now in terms of entitlements and what's going to happen when the boomers start to retire, and just as one example, there are others, but everybody is afraid to talk about it, and the common statement each year is that well, we can deal with that as soon as the election is over.

That's what elections are supposed to about. And that has to do with leadership, and it has to do with not just being a sponge and receiving what you're getting out there and your poll numbers tell you, but actually leading and I think that politicians underestimate the ability of the American people to appreciate something like that, and I think the precise answer to your question, I think most people will turn it off, will turn most all of it off, and probably until sometime after the world series and the important things are over with. And then they'll see who's standing and the election will actually depend upon things that haven't happened yet. George Mitchell: The polls tell us consistently two things. The American people say they detest negative campaigns, and secondly, the American people are consistently persuaded by negative campaigns. The challenge of leadership is to reconcile these conflicting views. Can I take a couple minutes to tell a joke -- not a joke, a story about this.

Leon and I became fast friends. We spent months together during our huge budget disagreement during the first Bush Administration, months and months and months, and we got a lot of publicity and it was almost all negative, oh, they're like kids in a sandbox scrapping away, and I used to go back to Maine every weekend and hold town meetings and when one Saturday a huge crowd assembled, disproportionately elderly, and the first guy got up and says Senator, I want to make a statement and ask a question.

He said to me, you are a disgrace. You represent us and we don't like the way you're representing us. You're doing a terrible job.

He said, I want to tell you, we're sick of all this bickering between you and President bush. We want you to go back there and settle this issue like

Gentlemen from Maine, as the two of you are. Then he said that's my statement.

Here is my question. So what are you fighting about? And of course when he made the statement, the crowd roared and approved. So it turned out that one of the biggest issues was Medicare funding, so I explained to him we're fighting over Medicare funding. When we finished the explanation, he said Senator, I want you to go back there and don't you budge an inch, and the crowd erupted.

So I went back with two clear messages. Settle the issue but don't budge an inch. And I think that's one of the consequences, and I think people don't like them, but they're influenced by them. Leon Panetta: Let me ask you both, if there were another -- god willing it won't happen, but if there's another terrorist attack, what will be the impact between now and the election?

We saw what happened in Spain. What is the likely impact of another September 11 on the race between President Bush and john Kerry? Fred Thompson: That's a very good question. I think there will be two competing factors if that happens, and one is the feeling that oh, my god, all this wouldn't Have happened if we'd not been so energetic abroad, obviously working to bush's detriment. The other one would be we're not going to show the people of The world that we're like the Spanish.

They're not going to decide who's going to be our President, these terrorists are not. I think you'll have those two competing things. I also think, it depends on when it happens. I think if it happened real close to the election, people would rally around the flag and that would benefit Bush. I think if it happened somewhat out from it, that that would probably work to his detriment. Leon Panetta: George. George Mitchell: that was a pretty cold political analysis of something so serious, but I guess we've got to think about that, it's so speculative, and I believe so dependent upon the circumstances at the time of the event, of the response, that one can really only guess, but I think Fred's analysis is probably fairly close.

I would have to say, guessing, without knowing the circumstances, that it's likely to help the President. People everywhere tend to rally around their national leader in a time of crisis.

Margaret Thatcher was under 20% in the polls when the Falklands war occurred.

She went up to 80%. You saw what happened with President Bush and September 11. You've seen that in Israel, with Prime Minister Sharon and indeed with Chairman Arafat. Arafat's poll numbers have been steadily going down and the only time they blip up is when the Israelis lob a couple of tank shells into his compound there, then they blip up, then they drop again.

So I think the immediate reaction would be rallying around the President or the leader at a time of crisis. Leon Panetta: what is the appropriate role of the federal government when it comes to outsourcing of jobs overseas? George Mitchell: I was a Senate majority leader and led the Senate to ratification of the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement and the World Trade Organization. The most severe criticism came from within my own party. But I believe that the record is clear that the people of this country have been the principal beneficiaries of the expansion of trade, the spread of stability and democracy that has occurred in the half century since the close of the Second World War. This is not to say that our trade policy has been perfect or without error or adverse consequences.

Indeed they have, but remember, most economic dislocations occur because of innovation in a dynamic free market economy, not as a consequence of trade agreements. I come from Maine.

We once had a thriving industry in New England with hundreds of people engaged in the manufacture of stage coaches. There is not one person in America now employed making stagecoaches. The people who lost their jobs and the towns where those jobs were concentrated were hard hit, but every reasonable person can conclude that the invention of the motor vehicle has been a dramatic benefit to our country as a whole.

Now we have to do a better job on environmental, health, and wealth fare, and labor standards, in other countries, where jobs are going, because there is an unfairness about the competition that exists. But it is the pursuit of an illusion to believe that if we can just somehow erect walls around our country, we're going to protect ourselves and improve our economic condition. We're not going to. It's like holding back the tide. We should direct our energies not to trying to create a fantasy world that won't benefit our people, but to doing a much better, more aggressive and more innovative job about mitigating the adverse effects that comes from trading with other countries. In so doing, we'll benefit ourselves and we'll benefit others with whom we deal. Fred Thompson: I think that the recent rise of protectionist sentiments are very detrimental potentially to our economy. I agree with Senator Mitchell 100% on what he said about free trade and the benefits, and it helps our people buy cheaper products. It helps other people in other nations who aspire to be economically successful, to lift their standard of living. And we gain in the process. Nations that trade openly are by and large successful nations.

Nations that do not, by and large are not successful. That's the whole thing for me. I do think that it would be a mistake to impose environmental and labor standards on these fledgling, some younger countries or small countries or poverty stricken countries, because I think the best thing we could do as a condition for free trade with us, the best thing we can do to alleviate those kinds of problems is to have free trade, and it's only helping lift them out of poverty that free trade will bring about that they will improve their environmental conditions, for example, not because of any mandates we lay on them. Leon Panetta: President Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney testified before the 9/11 commission with no press coverage. Should the public know what was said and why? Fred Thompson: I think that there's something to be said for a certain amount of informality in a situation like this. They're trying for -- in a way, I would like to have had a transcript of it, but I think the main thing is to impart information, and if they're really interested in information, on having a frank back and forth and give and take as they did with the President and Vice President as they did with President Clinton and Vice President Gore, I think this forum and this format with regard to this commission, which I think is a bipartisan commission and nobody is going to get away with anything of any substance, I think, is a decent format to do that in. And I incidentally think that from all the turmoil that they've had from time to time and controversies that the commission has had, that a couple of important things are going to come out of it.

One is that the American people now know what those of us who have been in the Senate, especially those of us who have been on intelligence Committees, and the American people, if they have been paying attention, should have already known, and that is that we have a great deficiency in terms of our intelligence capabilities and what that leads to, and I think President Bush has now said that we need reform, we need to do some things differently. He has somewhat of an excuse, I think, in a way seven months, how much can you do it, takes longer and longer to get a team together, each succeeding President it takes longer and so forth.

Up to a point. But it became obvious some time ago that we had great deficiencies there and it had to be done. I think he's making that statement now, one that's long overdue, quite frankly, and I think a lot of it had to do with the fact that now everybody has seen how bad the situation is and what the consequences are. The other thing that's coming out of the 9/11 Commission is the consensus, it seems like by the Commission, that sometimes, sometimes pre-emptive action is something you have to do. We can debate over when and where and so forth, but the President is taking a lot of criticism, by the majority of the Commission, it seems, for not having done more before September 11 in terms of -- it could only be described as, pre-emptive terms. Leon Panetta: what do you think, George? George Mitchell: Well, I like and respect Fred so much, I'm always embarrassed to disagree with him, but on this I do. I think Clinton, Gore, Bush and Cheney should have testified, their testimony transcribed, televised if necessary. This is a democracy, not a monarchy. The President is the President. He's not a king, even though we treat Presidents like kings in this country. And if bill Clinton as President could be compelled to testify under oath on the record before TV about his sex life, I think the current President could testify under similar circumstances --. [applause] George Mitchell: -- Let me finish -- about what is one of the greatest tragedies in American history, and I think the gravity of the event by itself should have been sufficient to require that kind of testimony. Leon Panetta: Let me ask Fred: how did a person who was a counsel become a movie actor? And then become District Attorney on "law and order"? Fred Thompson: First of all, I appreciate the compliment. I once pointed out, I said I just happened into this thing, I never took an acting lesson.

They said we know, we saw it. We've seen your work. No, it's like most things that have happened of any importance in my life, total serendipity. I was practicing law, they made a movie about a case I had and I played myself in the movie, so it was a terrible mistake that they made, letting me in on the inside there, because I wouldn't turn them loose, so I did 18 features and then for the Senate, and I often say that with all of the political activity in Hollywood, that I had to leave the Senate and go back into show business to get my points heard again. Leon Panetta: George, let me ask you about your role as chair of Disney. What was tougher, being majority leader or being Chair of the Disney Board? George Mitchell: well, I didn't realize that, but the good lord has a way of working mysteriously and pulling strings, so my work as Senate Majority Leader, my work five years in Northern Ireland working on a peace agreement, and the one year I spent in the Middle East, were all preparations for my current position. Fred Thompson: You know, it just occurred to me, he's Disney. I still try to make a movie occasionally. I may be working for him. I want to apologize for anything -- George Mitchell: I'll tell you one thing. I think you're a hell of a Senator and I think you're a great actor. Fred Thompson: thank you very much. George Mitchell: can that substitute for money, as psychic remuneration, the applause? Fred Thompson: Much more so. Leon Panetta: Well, you're both not only great actors but great public servants, and we have been honored this evening to have had the benefit of your views. These are tough issues that this country is facing, and the important thing we want to do is to ensure that everyone here and everyone, for that matter, throughout America, participates in this process. The most important thing in democracy is that we're willing to talk about these issues and not be afraid to talk about them, because probably the ultimate of patriotism is the willingness to debate and discuss our differences, and we do that here at the Panetta Lecture Forum, and we thank both of you for your participation.

[applause]

http://www.panettainstitute.org/lib/04/mitchell_thompson.htm

TIME TO PUT UP OR SHUT UP

Click a Topic to Read and Research and then scroll down

- 2008 Campaign (2)

- awards (3)

- Commentary (1)

- Federal Law (28)

- Federalism (2)

- Foreign Policy (12)

- Fred Thompson (114)

- interview (1)

- official position (22)

- Qualifications (1)

- Record (1)

- reports (7)

- speeches (3)

- Tennnessee Law (14)

- videos (8)

- Vote Comparison (1)

- writings (32)

Click A Post In The Archive- star=full report. Click topic to bring up in new page

-

▼

2007

(116)

-

▼

April

(113)

-

▼

Apr 22

(29)

- Thompson Bill to grant Attorney General Discretion...

- Thompson Fights to Eradicate Tax Penalty on Public...

- More on Thompson Homeland Security Amendment and I...

- Thompson advocates increased flexibility for Homel...

- Senator Thompson; Federal Management Reform and th...

- Thompson Amendment for Airline Security

- Thompson's 2001 Assessment of Federal Agencies

- House Adopts Thompson Aviation Security Amendment

- Thompson Legislation to Protect Federal Informatio...

- Thompson Federal Regulatory Improvement Act of 1998

- Thompson on IRS Accountability to Public

- Levin-Thompson Regulatory Improvement Act

- 1998- Thompson Calls for Arms and Dual-Use Export ...

- Congress Passes Thompson Legislation Promoting Pub...

- Thompson-Warner Bill to Allow Homeland Security Ag...

- Thompson Provision On Public Regulation Passes

- Thompson Applauds Mineta Airport Security Plan

- National Security Workforce Legislation

- *Preface from Thompson's Report into Financial Cam...

- *Recommendations from Senator Thompson's Investiga...

- Thompson's Freedom to Manage Package to Reform Gov...

- Thompson Amendment ensured to protect privacy on g...

- Companion to Management Issues Report

- Statement on Antrax through the Mail

- "Restoring the Balance" Award

- Statement on the Export Administration Act

- Comments on IRS Mismanagement of Funds

- Oped on the Future of the Independent Counsel Act

- Leadership Challenges in the 21st Century: Panetta...

-

▼

Apr 22

(29)

-

▼

April

(113)

Meet Senator Thompson

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Fred Thompson

Former U.S. Senator (R-TN)

2 comments:

Good day !.

You may , probably curious to know how one can manage to receive high yields .

There is no initial capital needed You may start to get income with as small sum of money as 20-100 dollars.

AimTrust is what you thought of all the time

The firm incorporates an offshore structure with advanced asset management technologies in production and delivery of pipes for oil and gas.

It is based in Panama with structures around the world.

Do you want to become a happy investor?

That`s your chance That`s what you really need!

I feel good, I began to get income with the help of this company,

and I invite you to do the same. It`s all about how to select a proper companion utilizes your money in a right way - that`s the AimTrust!.

I take now up to 2G every day, and my first investment was 500 dollars only!

It`s easy to get involved , just click this link http://fafysytas.freewebportal.com/uqisufu.html

and lucky you`re! Let`s take our chance together to feel the smell of real money

Hi!

You may probably be very curious to know how one can make real money on investments.

There is no initial capital needed.

You may begin earning with a sum that usually is spent

on daily food, that's 20-100 dollars.

I have been participating in one project for several years,

and I'm ready to let you know my secrets at my blog.

Please visit my pages and send me private message to get the info.

P.S. I earn 1000-2000 per daily now.

http://theinvestblog.com [url=http://theinvestblog.com]Online Investment Blog[/url]

Post a Comment